Under the guidance of teacher Mary Noh, the Early College High School Humanities 9 class is embarking on an impressive and deeply immersive journey into the ancient world as they design their own original civilizations from the ground up.What began as a study of early river valley civilizations—Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, the Shang Dynasty, and Ancient Egypt—has evolved into a hands-on, creative, and deeply analytical project that challenges students to think like historians, archaeologists, authors, and museum curators all at once.

Through their research, students have discovered that every civilization, no matter the time period, shares certain foundational components. They explored how these ancient societies developed systems of language, created religious beliefs to explain the natural world, formed governments to organize people, invented early technologies, established job specialization, and produced art and cultural expressions that reflected their values. After examining these common traits, the class shifted into a unique thought experiment: imagine being stranded in an unfamiliar land, completely removed from modern technology, conveniences, and cultural traditions. What would it take to build a civilization that not only survives but eventually flourishes?

With that challenge in mind, students began sketching out the earliest elements of their imagined societies. They discussed what natural resources might be available, what challenges their environments would present, and what values their people might prioritize. From there, they moved into creating the physical and cultural building blocks of their civilizations. Students designed artifacts, tools, symbolic items, and pieces of art that might someday be “discovered” by archaeologists hundreds or even thousands of years in the future. Each artifact needed to connect to the larger civilization and help tell the story of how these societies formed and evolved.

To deepen their understanding of early literary traditions, the class read The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest recorded works of literature in the world. Through this text, students explored how ancient civilizations created myths to convey lessons, explain the unknown, and preserve cultural beliefs. The story also provided insight into how early societies viewed leadership, religion, friendship, and mortality. This literary connection will serve as inspiration as the students begin writing their own myths—stories that will become central to their civilizations’ emerging religions and cultural identities.

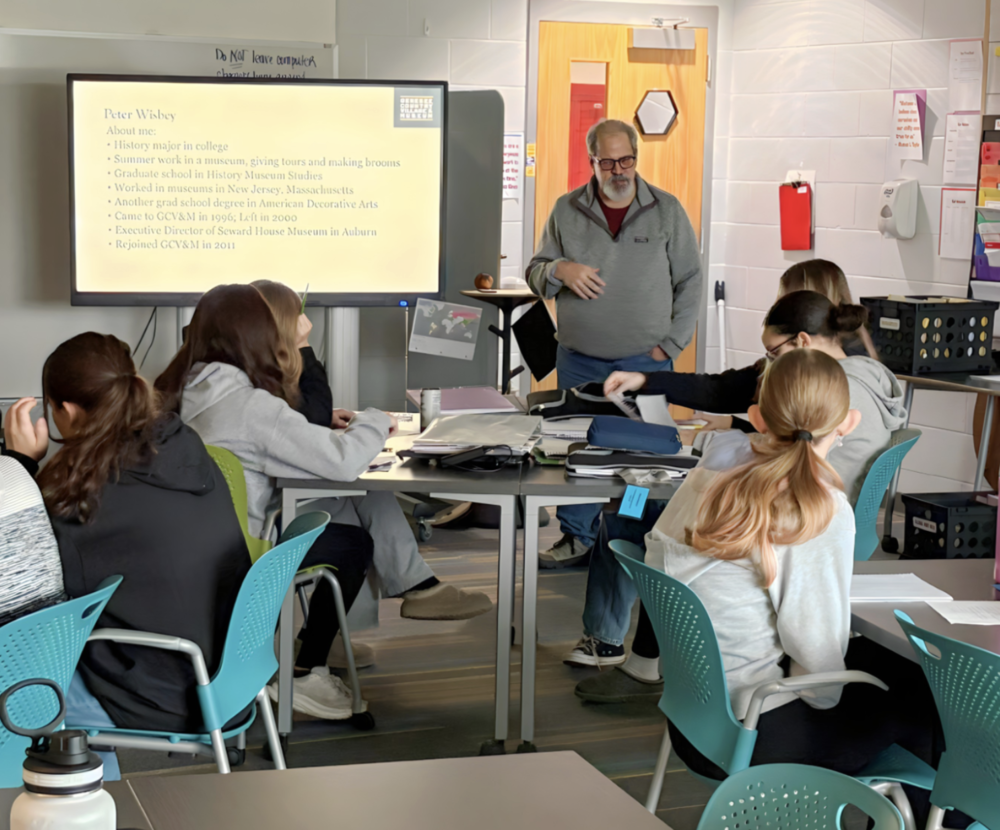

Because the final component of the project is to design a small-scale museum exhibit showcasing their civilizations, the class had the opportunity to learn from someone with a lifetime of experience in museum curation. Peter Wisbey, a seasoned curator from the Genesee Country Village & Museum, visited the classroom to share his expertise, his personal journey, and his passion for storytelling through objects.

Wisbey has been in the museum field for more than 40 years, and his insight gave students a rare behind-the-scenes understanding of what it means to preserve and interpret history. He shared stories about his very first visit to the museum in 1977—a moment he still remembers clearly—and how it eventually led him into a lifelong career centered on artifacts and their stories. After beginning his professional path at the Genesee Country Village & Museum, Wisbey later became the director of a historic house museum in Auburn. After almost a decade away, circumstances brought him back to Genesee Country Village & Museum, where he continues to help shape how visitors experience the past.

During his visit, Wisbey explained that the museum includes 67 buildings, each one representing a different time period, story, and historical significance. That means 67 unique narratives—and countless decisions about what artifacts to show, how to classify them, and how to share them with the public. “Curators know the most about your exhibit,” he told the students. “But it’s up to you to tell a compelling story.” His message emphasized that while artifacts hold information, storytelling is what brings them to life.

Wisbey also described the wide network of people who work behind the scenes to make the museum function. From historians and educators to costumed interpreters and artisans, every person helps contribute to the storytelling experience. He highlighted a master weaver who has been demonstrating traditional weaving techniques and sharing stories at the museum for 50 years, illustrating how one person’s dedication can preserve cultural heritage across generations.

To help students understand the power of close observation, Wisbey brought a unique activity to the classroom. He handed each student a pen—no two pens alike. One came from Nashville, another from a museum in Pennsylvania, and others had subtle variations that suggested different origins or purposes. The students’ challenge was to study their pen carefully and analyze its details, then explain what made it unique. In doing this, they practiced the same skills a curator uses when examining an artifact: noticing craft, identifying clues about its history, and imagining the stories it might hold. A simple pen became a gateway to understanding how objects—even ordinary ones—can carry meaning and connect to a larger narrative.

This activity connected directly to the students’ civilization project. After studying real and imagined artifacts from ancient cultures, they were now challenged to think critically about the ones they created themselves. What story does this object tell? What values or beliefs does it reveal? Why would future archaeologists find it important? Wisbey reminded them that curators must constantly make decisions about which artifacts best represent an exhibit, and students will face similar choices as they build their museum displays.

In the weeks ahead, the Humanities 9 students will continue developing the major features of their civilizations. They will finalize governmental structures, write original myths that explain natural phenomena or cultural traditions, and determine which artifacts best showcase the identity of their societies. Each piece—whether a carved symbol, a tool, or a cultural artwork—will contribute to the story their civilization is trying to tell. And thanks to Peter Wisbey’s visit, students now have a clearer understanding of how museum exhibits are built, how curators think, and how powerful storytelling can be when sharing the history of a people.

By the end of this project, students will not only have created civilizations of their own design, but they will also have learned how to present those civilizations in thoughtful, engaging ways—much like the professionals who preserve history every day. Through analysis, creativity, and guidance from an expert curator, these ninth-graders are gaining a deeper appreciation for the past while discovering how to bring their imaginative worlds to life.